Balancing Interfering Training Adaptations within Hockey Training Periodization

Interference effect defined: When concurrently training both capacities of endurance and strength, interference may occur when the development of one capacity hinders the development of another capacity compared to training either capacity independently and in isolation.

Hockey separates itself from many sports in the sense that it is incredibly mixed energy system demand and requires the athletes (at a high level anyways) to be excellent in several physical disciplines.

In particular, hockey requires high intensity skating speeds and involves movements that demand explosive, maximal effort actions such as checking, shooting, high velocity direction change, and many other forms of body contact (defending the net, gaining control of the puck, etc) + body movement.

Staying within the principle of specificity, this will require very well thought out training blocks incorporating the development of aerobic capacity, strength, and power simultaneously. Doing this may seem simple to some, but to the knowledgeable strength and conditioning coach, it can be a nightmare due to the separate training stimuli and conflicting adaptations.

In the development of athletic potential for hockey, training blocks are constructed and periodized to train the functional components critical to sport success. This means, analyzing the sports demands from a sport physiology perspective and mimicking them within the gym. In other words, keeping the good and throwing out the bad.

Training time can be rare in most cases due to work schedules, school schedules, team schedules, travel, among many other things which makes the proper utilization of this training time vital for hockey players.

You want to get the maximum return on investment (ROI) each time you step foot in the gym. Much of this investment has to do with the structure of how you are timing your training sessions to gain adaptations in multiple qualities.

Now, what the heck do I mean when I am talking about balancing conflicting adaptations?

Well, when you train you create a stimulus, how your body adapts to that stimulus is what you will gain from the workout.

For example, lifting heavy weights creates the stimulus to build strength, you getting stronger is the adaptation you gain from that stimulus/workout.

In a sport like hockey where you need to be good at essentially everything, you can run into some issues. Interference can occur during the “adaptation” process after a workout when the body is trying to adapt if you perform another activity.

For example, let’s say you lifted heavy weights today to build strength, and then immediately after went for a long jog. In one case you’re training for strength, and immediately after you’re training for endurance. This can cause the body to say:

“I’m not sure exactly what it is you want me to adapt to, so I’m going to find some grey area in between the two”

What ends up happening is you really don’t get exceptionally good at either quality or gain maximal adaptations from either workout that day. This can decrease your overall rate of athletic development, but also is definitely decreasing your ROI per workout.

You want to invest your time in the gym, not spend it.

When something as simple as a timing strategy can improve your results, you should be all over it.

The first relevant observation of the interference effect within strength training was seen by Hickson et al in 1980. This was a clinical trial where three groups were assigned separate training guidelines.

One group was to strength train only, another group was to perform only aerobic work, and a third group was to perform both strength training + aerobic work.

After 10 weeks, the strength-only group improved their strength and the endurance-only group improved their endurance — while the combination strength-endurance group only gained significant adaptations towards endurance and not strength.

It was then concluded by Hickson that muscular changes induced from strength training are opposed to the changes induced through concurrent endurance training and that muscle may not be capable of adapting to both stimuli at once. Read that line over three times if you have to, it is critically important that you understand this.

After this, this prompted plenty of research from the physiology community to gain a better understanding of this phenomenon and up to this day we have learned a whole lot about what happens mechanistically within the muscle when athletes try to do everything at once.

Let’s take a step back for a second though and just look at this from a common sense perspective. I mean, it makes sense, right?

Powerlifters don’t run marathons to get better at powerlifting. That would be dumb.

Likewise, ironman athletes aren’t running ironman races to improve their deadlift.

These are completely different training adaptations and seasoned athletes will tell you that once they are off the beating path within their given sport that it can cause a decrease in performance.

This isn’t so simple with hockey though, and why it often goes overlooked.

You see, powerlifting and marathon running are obvious, blatant examples because they are single energy system demand sports.

Powerlifters need lots of strength, and that’s about it.

Marathon runners need all kinds of endurance, but that’s it.

Whereas hockey players need both strength and endurance if they want to perform to their potential.

So, how the heck do we do this when conflicting adaptations are staring us right in the face?

Let’s have a look at some complications and see what we can do about them.

First and foremost, it’s important to note that the interference effect does not apply in untrained individuals. If you are completely untrained and are reading this blog looking for information on how to properly strength train for hockey — You can train for both strength and endurance at the same time and make gains in both simultaneously.

Newbie gains come in all shapes and sizes and you can pretty much get away with anything, enjoy it while it lasts.

As you progress in your training career and you have spent some more time under the bar, the interference effect becomes a very real thing and will become more and more important the more advanced you get. Meaning, there is a linear increase in how detrimental the interference effect will be to your adaptations from exercise the more physically advanced you become.

The stronger and more advanced you are, the more “over doing” your endurance work is going to negatively affect your strength.

From a mechanistic standpoint, there are many ways in which conflicting adaptations can present themselves, it’s not all just training program design:

Energy balance (calories in vs. calories out): If your “calories in” are less than your “calories out” — this is going to drastically oppose gains in muscle size. These are normally the guys who claim themselves “hard gainers”.

Look, if you’re not eating enough, there is no way you are going to gain weight. That also means if you’re not eating enough, it is going to be extremely hard putting on any amount of respectable muscle mass. It is very well known that during periods of negative energy balance (calories in being less than calories out) protein synthesis is drastically reduced. Very strong conflicting adaptation here without even a discussion of your training schedule. On one hand you say you want to gain mass, but on the other you’re not providing the fuel to do so.

Another view at energy balance side stepping away from the weight issue is the hormonal consequences. If you’re not eating enough to support your activity levels plus gain weight, than your body is systemically catabolic (tissue breakdown, as opposed to build-up) from a hormonal signalling sense. Strength training is very well known to stimulate anabolic hormones and enzymes within the body, but if you’re in a negative energy balance this stimulation will be modest at best — inducing a greater overall cortisol presence and decreased overall testosterone levels.

Improper recovery and fatigue management: If you are currently in a state of overreaching or overtraining, the body’s anabolic signalling systems will be significantly down regulated, creating a very evident conflicting adaptation. A state of overtraining results in exhaustion of the nervous, muscular, hormonal, and immune systems which collectively negates continuing adaptions from exercise. Time off is required is almost all cases for almost everyone in this scenario.

mTOR vs. AMPk activation: I talked a bit about this here

The data on this type of signalling is both fantastic and fascinating.

Essentially, how your body tells your muscles to get larger and get stronger is a highly complex and intricate process that involves many enzyme reactions that are initially kicked off from the training stimulus.

Strength and hypertrophy training kicks off through an anabolic pathway known as mTOR. When mTOR is stimulated, it creates any and all things anabolic and creates adaptations in the body to strength training. That is, building muscle mass and strength.

But, if you go on a long jog later on that day, your body is more like:

“Ok, so he is also trying to gain endurance. I don’t want to put on as much muscle mass as I can because more muscle mass would be counterproductive to endurance. Let’s stop the recovering process from building more muscle, and instead create cardiovascular aerobic adaptations”

This is done through AMPk.

AMPk is a cell signalling pathway that creates all things endurance adapted in the body. Such as improved use of fat for fuel, increased mitochondrial density, increased efficiency utilization of energy substrates, etc.

AMPk doesn’t sound so bad, right?

But here’s the kicker, AMPk shuts off mTOR. This is why you don’t see guys who strength train and run all the time ever get big. AMPk blocks the anabolic signalling cascade that mTOR is trying to create.

So, what do we get?

Endurance adaptations and not so much strength adaptations. Sound a whole lot like the research gathered in 1980 from Hickson, doesn’t it?

These two dominant cell signalers are the heart at which all conflicting adaptions lie in.

Motor unit recruitment: The nervous system recruits motor units which house many muscle fibers in which to contract during a given movement. Some research has shown that high power output movement’s neural pathways for recruitment can be dampened through excessive endurance training. Hockey players depend on this type of explosive muscle recruitment (explosive skating, shooting, body checks, etc) so a conflicting adaptation residing within the neurological system is of significant importance to us.

Balancing Conflicting Adaptations For Optimal Results

Now that we have gone through the several pathways in which conflicting adaptations may present themselves, let’s talk about how we can prevent this from happening.

I always like to talk about the “why” first instead of just jump straight into the strategy to give you more knowledge and context to the subject.

For example, conflicting adaptations from motor recruitment, energy balance, fatigue management, and enzyme signalling are all different in their own unique way. For you to go out into the world in your own training knowing what is wrong gives you much more power than just strategies. Without context, strategies mean nothing because you wouldn’t know when to apply what.

Knowledge is power, and I want you to be the best athlete you can possibly be.

With proper manipulation of your training scheduling, you can gain adaptations from multiple disciplines at once, but we can only do this once we know what moves we need to make.

Keeping similar adaptations in line with each other decreases and/or minimizes conflicting effects.

For example, high load resistance training will not be meaningfully negated by high intensity interval training (HIIT).

Why?

The high load strength training (less than 5 reps) is focused almost exclusively on the nervous system and not the muscular system.

Whereas the HIIT is highly muscular dependent and creates metabolic demands mainly from the muscles themselves. In the end, they really aren’t competing.

Neural strength work + HIIT gets a check mark.

Outside of neural and HIIT work getting a green light on the same day, I’m not a fan of combining any other forms of training too close together on the same day. Strength and hypertrophy work can get chopped down in a hurry by AMPk if you combine it with lower intensity conditioning work.

Also to keep in mind for the in-season, your practices largely account for low intensity endurance work. So if you’re training, ideally this should not come right before practice. From a physiology perspective, that can be quite conflicting. Strength training vs. aerobic work.

Knowing this information, it becomes important for you to prioritize what you want to do. I’m not working with you 1-on-1, so I’m not sure what you’re good at and what you’re not.

Individual performance schedules should be laid out based on your personal schedule to first prioritize what you’re bad at.

Training volume will be allocated to where it needs to be to bring up your performance and balance the adaptations as best as possible.

You need to take responsibility for yourselves here and be honest with yourself when prioritizing what you’re good at and what you’re not. From here, create a schedule that minimizes complications towards what you need the most work on.

Here are some quick guidelines to make sure you’re digesting the information and making the right moves:

• In a perfect world, each workout would have its own day. Strength training would be on its own day, conditioning would be on its own day, and skill work would be on its own day.

• When this isn’t possible, separating the workouts by 6-8hrs is recommended as to minimize interference.

• Prioritize your goals and do your best to minimally interfere with what you suck at most. For example, if you’re weak don’t do a long run after training. Get your schedule and priorities in check to optimize your strength.

• Interference can come also from poor recovery, overtraining, and under eating — so keep these in check.

• If you need to work on endurance the most, train endurance any time you wish.

• If you need to build muscle and strength the most, train it on its own day — or if you absolutely have to train it on the same day as conditioning do your conditioning first in the AM and your strength training in the PM 6-8hrs later.

• If you need to build muscle and strength the most and you need to train it on the same day as conditioning but you can’t do your conditioning 6-8hrs earlier, still doing it before your strength training is better than afterwards. (strategy with these last two suggestions are to keep mTOR from being completely shunted by AMPk by training it last so that it may remain “on”)

• Strength and muscle building are much more effected by conflicting adaptations than endurance.

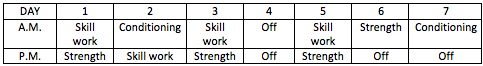

To send this home, here’s an example schedule for you guys to draw from should you have a super busy schedule and you’re looking to optimize everything you can:

Thanks for taking the time to read this hockey training blog post. If you want to become a better hockey player check out our Hockey Training Programs designed to make you a faster, more explosive, and all around better player!

Great info here as usual Dan! I have learned so much from your posts and look forward to using this knowledge to train smarter and get the best results of my life. Thank you

Good stuff, Dan. And, one observation I’ve made over some 40-years in coaching from beginners through college..

I have become less inclined to use strictly aerobic work with my older players, preferring to get close to that training effect with something like an hour of rather upbeat/uptempo drills or exercises.

That observation… Having watched a number of talented and speedy teens enter a fall soccer season, the ones who played under a coach who ran the players to death almost daily over several months, had those speedy kids losing their quickness by the time they got to the ice.

Good staff to consider. Thank you Dan